Diagnostic Reasoning: Sepsis Framework

The Reflex Response Trap

You’re reviewing the referrals from ED. A 68-year-old has come in with a temperature of 38.7°C, heart rate 105, and feeling generally unwell. The working diagnosis is “sepsis ?source.” Blood cultures have been taken, and they’ve already received broad-spectrum antibiotics in A&E.

Sounds reasonable? Fever, tachycardia, feeling unwell – you should definitely consider sepsis (and it’s hard not to, considering all the marketing from the “think sepsis” campaign). It would be tempting to start the Sepsis Six and move on to the next patient.

But when you examine them a little more closely, you notice there’s a morbilliform rash across the trunk that appeared two days after starting carbamazepine for trigeminal neuralgia. No cough, no urinary symptoms, no abdominal tenderness. Observations are stable apart from the tachycardia and fever. The chest is clear, there’s no costovertebral angle tenderness, and the abdomen is soft throughout.

The fever in this patient could potentially be a drug reaction, not an infection at all.

Fever doesn’t automatically mean sepsis, but it’s easy to assume it does when you’re busy and the pathway seems straightforward. The problem is that reflex treatment can delay the actual diagnosis and expose patients to unnecessary antibiotics (think antibiotic-associated diarrhoea or C. diff) or worse, make you miss something that needs completely different management.

Why We Jump to Infection

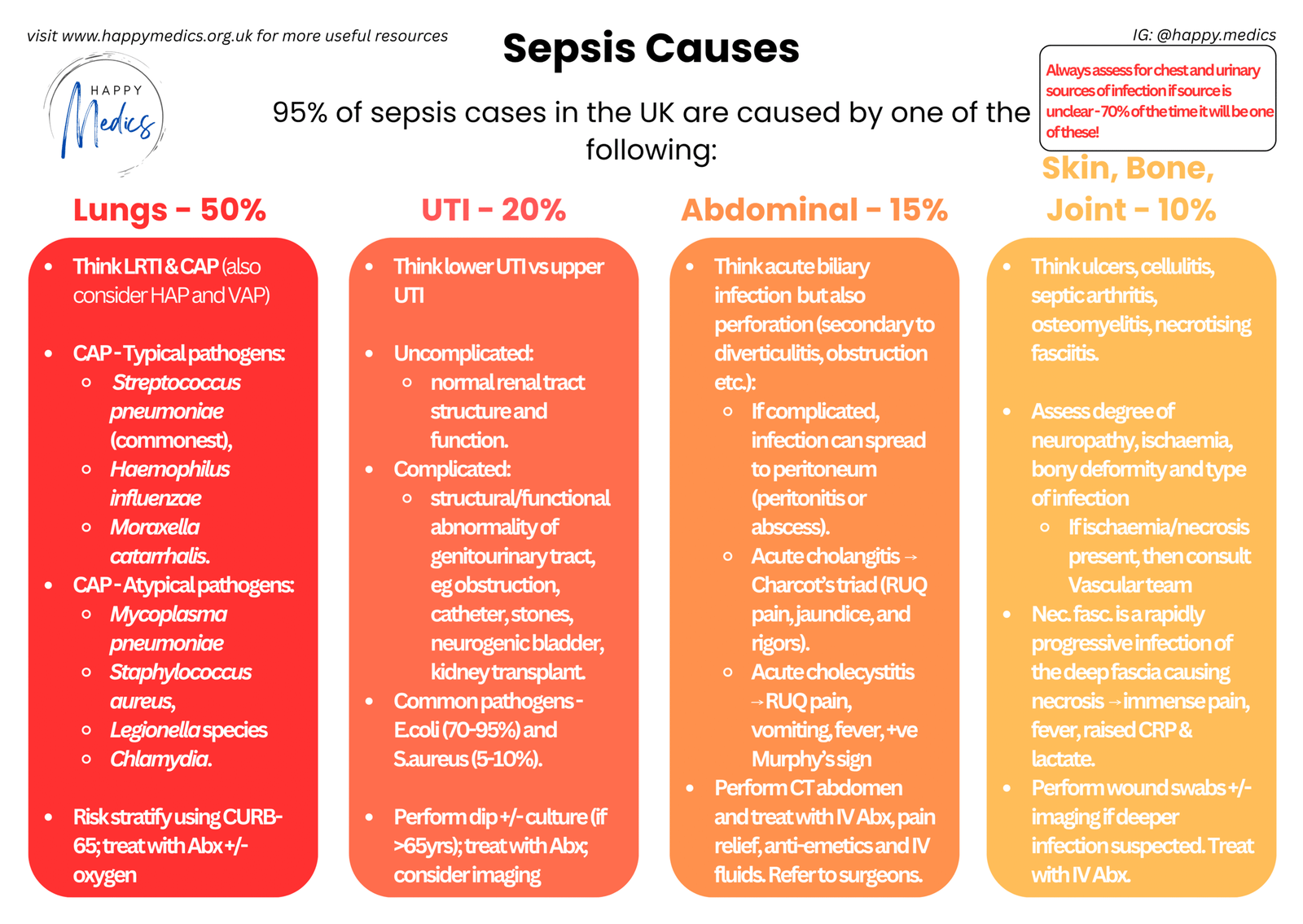

When someone has a fever, your brain immediately pattern-matches to infection. It’s the most common cause by far. Lungs account for 50% of sepsis cases, urinary tract 20%, abdominal sources 15%, and skin/bone/joint 10%. There are clear protocols to follow: fever → think sepsis → start antibiotics. Simple, fast, defensible.

This works a lot of the time, which is exactly why it’s become the default. But fever has a surprisingly broad differential beyond infection, and anchoring too quickly on sepsis means you might not consider the alternatives until much later (and by then the patient may have come to some harm due to diagnostic delay).

Certain clues should prompt you to pause: rigors dramatically increase the likelihood of bacteraemia (likelihood ratio 4.7), whereas the absence of any fever makes bacteraemia much less likely. But here’s what catches people out: 5% of patients with confirmed bacteraemia are completely normothermic, and a normal white cell count doesn’t rule out bacteraemia either (it’s only 28% sensitive).

The other issue is timing. The latest sepsis guidelines actually give you quite a bit of breathing room for low-risk patients; you can defer antibiotics for up to 6 hours if you need time to identify the actual source, perform investigations, or arrange source control. That window allows you to be more thoughtful rather than reflexively reaching for broad-spectrum cover.

What you need during this extra time is a systematic way to consider what else could be causing the fever before you commit to treating infection.

The IMADE Framework

- This mnemonic covers the main categories of fever beyond straightforward infection. It forces you to pause and ask: is this definitely sepsis, or could it be something else entirely?

- I – Infection

- M – Malignancy

- A – Autoimmune

- D – Drugs

- E – Endocrine / Embolic (DVT/PE)

- Running through IMADE takes less than two minutes and stops you from anchoring prematurely on infection. With that said, if infection or sepsis are strongly suspected, then don’t delay treatment unnecessarily.

When you’ve confirmed it’s infection: Once you’ve established that it probably is infection, you’ll want to narrow down the source. The comprehensive sepsis framework shows you where to look: lungs (most common), followed by urinary tract, GI tract, skin/bone/joint. Always assess for chest and urinary sources first as 70% of the time it’ll be one of those two. The framework also breaks each category down further with typical pathogens, complications, and investigation strategies. Think of IMADE as your initial screen to confirm you’re dealing with infection at all (if unclear), whilst the detailed framework helps you identify the specific source once you’ve ruled out the non-infectious causes.

IMADE in Practice

- Let’s go back to that 68-year-old with fever, tachycardia, and the rash. Work through IMADE systematically before committing to sepsis.

- I – Infection?

- Where’s the source? Check the usual suspects: chest (50% of sepsis), urinary tract (20%), abdomen (15%), skin/soft tissue (10%). In this patient: chest clear, no urinary symptoms, abdomen soft, no obvious wound or cellulitis.

- But there’s no clear focus. That should make you pause.

- M – Malignancy?

- Any constitutional symptoms? Weight loss, night sweats, lymphadenopathy? Check for organomegaly. Malignancy can cause fever through tumour necrosis or paraneoplastic syndromes. In this case, no red flags for malignancy.

- A – Autoimmune?

- Any history of autoimmune disease? Joint pains, rashes, unexplained organ dysfunction? Conditions like SLE, vasculitis, or Still’s disease can present with fever. This patient has no history and no suggestive features.

- D – Drugs?

- This is the key question. What medications were started recently? Our patient started carbamazepine two days ago, and the rash appeared shortly after. That’s a massive red flag.

- Drug fever is common (antibiotics, anticonvulsants, allopurinol). The rash suggests DRESS syndrome (Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms). This isn’t sepsis—it’s a drug reaction that needs the carbamazepine stopped immediately, not antibiotics escalated.

- E – Endocrine / Embolic?

- Thyroid storm? Check for goitre, tremor, disproportionate tachycardia. DVT or PE causing fever? Swollen leg, chest pain, shortness of breath? In this case, neither fits.

- I – Infection?

After working through IMADE, the most likely diagnosis is drug-induced fever (DRESS syndrome), not sepsis. The appropriate management is to stop the carbamazepine, monitor for end-organ involvement, and consider steroids rather than escalate antibiotics.

Without IMADE, you might have anchored on “sepsis ?source,” changed antibiotics, and delayed the actual diagnosis.

Key Actions: What You Must Do

Take a focused history before assuming sepsis:

- New medications (including OTC and recent antibiotics)

- Constitutional symptoms (weight loss, night sweats)

- Recent travel or unusual exposures

- Risk factors for thrombosis (surgery, immobility, malignancy)

- Personal or family history of autoimmune disease or malignancy

- Presence of rigors (teeth-chattering chills = much higher likelihood of bacteraemia)

- Note: 5% of bacteraemic patients are normothermic

Examine systematically, focusing on common sources first:

- 70% rule: if source unclear, focus on chest and urinary tract first

- Look at skin for rashes or injection sites

- Examine all line insertion points (even if they look clean)

- Palpate for lymphadenopathy and organomegaly

- Check for costovertebral angle tenderness

- Easily missed sources: mastoiditis, sinusitis (with NG tubes), cholecystitis

Use the 6-hour window strategically for low-risk patients:

- Criteria: no vasopressor requirement, lactate <2 mmol/L, no organ dysfunction

- Use time to examine properly, send cultures, arrange imaging, consider non-infectious causes

- Targeted antibiotics beat empirical broad-spectrum cover

Check pulse pressure and assess perfusion:

- Wide pulse pressure (warm extremities, bounding pulses, brisk refill) = high cardiac output → distributive shock (sepsis)

- Narrow pulse pressure (cool extremities, weak pulses, sluggish refill) = low cardiac output → hypovolaemic or cardiogenic shock

If no source found, actively reconsider the diagnosis:

- Run through IMADE systematically rather than defaulting to “sepsis ?source”

- Check TFTs and ECG if disproportionate tachycardia

- Review medication chart for recent additions

- Consider autoimmune screening if suggestive features

- Arrange CT if considering occult malignancy or intra-abdominal source

Remember overlapping diagnoses are common:

- Patients can have sepsis plus another condition (e.g., DVT with cellulitis, drug fever with UTI)

- Don’t assume finding one cause excludes others

- If clinical picture doesn’t fit or patient not responding as expected, reconsider

When in doubt, discuss with a senior:

- Prolonged fever (>7 days), recurrent fever, or atypical features warrant senior input

- Don’t just escalate antibiotics—step back and reconsider systematically

Reference: NICE guidelines on management of sepsis

Three Things to Remember

✓ Not every fever is sepsis – run through IMADE before reflexively starting antibiotics, especially if the clinical picture doesn’t quite fit or you can’t identify an obvious source

✓ Chest and urinary sources account for 70% of sepsis cases – if the source isn’t immediately clear, focus your examination and investigations there first before looking elsewhere

✓ Low-risk patients give you time to think – you’ve got up to 6 hours to defer antibiotics if needed for investigations or source control. Use that window to get the diagnosis right rather than rushing to broad-spectrum cover

About the Author:

Dr Ahmed Kazie is a resident doctor in Acute Medicine and founder of Happy Medics. He teaches systematic diagnostic reasoning through clinical frameworks, helping other resident doctors build confidence in managing acute presentations.

Instagram | Subscribe to Newsletter | Join the AMC Waitlist