Diagnostic Reasoning: Headache Framework

The Reassuring Trap

A 45-year-old woman presents to ED with a severe headache that started suddenly two hours ago. She describes the severity as 10/10. Her observations are stable, and she’s neurologically intact on examination.

Your System 1 brain immediately thinks: migraine? Tension headache? She’s awake, talking, no focal neurology – probably benign.

But before you anchor on that reassuring impression, there’s one question you need to ask first: is this headache new or old?

This is a very important question to consider in a headache assessment and it will help you to determine whether or not you reassure the patient, discharge them home with safety-netting advice, or whether you urgently investigate for life-threatening pathology. Let’s discuss the headache framework.

The 1% Problem

Less than 1% of headaches are life-threatening. That’s reassuring from an epidemiological perspective, but it creates a diagnostic challenge: how do you identify that rare 1% without over-investigating the other 99%?

The answer isn’t to scan everyone with headache; that’s neither practical nor good medicine. But it’s also not acceptable to miss emergency causes because you assumed benign pathology based on a normal examination.

What you need is a systematic approach that reliably separates high-risk presentations from low-risk ones. That’s where the new versus old framework comes in.

The System 1 Trap

Headache is one of the most common presentations in acute medicine, and System 1 knows this. Most headaches are benign: migraine, tension headache, medication overuse. Your pattern-matching brain can default to “probably primary, probably safe.” But headache also accounts for some of the highest-stakes misses in emergency medicine: subarachnoid haemorrhage, meningitis, venous sinus thrombosis, arterial dissection.

About 25% of patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage are initially misdiagnosed, and the patients most likely to be missed are those with milder presentations, i.e. the ones who look reassuring, who are talking normally and who have normal observations. When SAH is missed, outcomes are dramatically worse: misdiagnosed patients are only about half as likely to have a good or excellent outcome compared with those diagnosed correctly on first presentation.

Dangerous secondary headaches can look deceptively benign early on; normal observations don’t rule out SAH, lack of fever doesn’t rule out meningitis, a clear neurological examination doesn’t rule out venous thrombosis or raised intracranial pressure. If you rely purely on gestalt (your gut instinct or System 1 thinking) or wait for obvious red flags to declare themselves, you’ll miss things.

You need a framework that forces you to ask the right questions before System 1 settles on a diagnosis.

The New vs Old Headache Framework

The single most important question when assessing headache is: is this headache new or old?

Old (chronic, recurrent) headaches tend to be primary headache disorders (migraine, tension headache, cluster headache). These are diagnoses of exclusion with characteristic features, and patients typically have a history of similar episodes. New (acute, first-onset) headaches are more likely to be secondary (caused by underlying pathology that often needs urgent treatment). Even if a new headache eventually turns out to be a first migraine, you can’t assume that until you’ve ruled out dangerous causes.

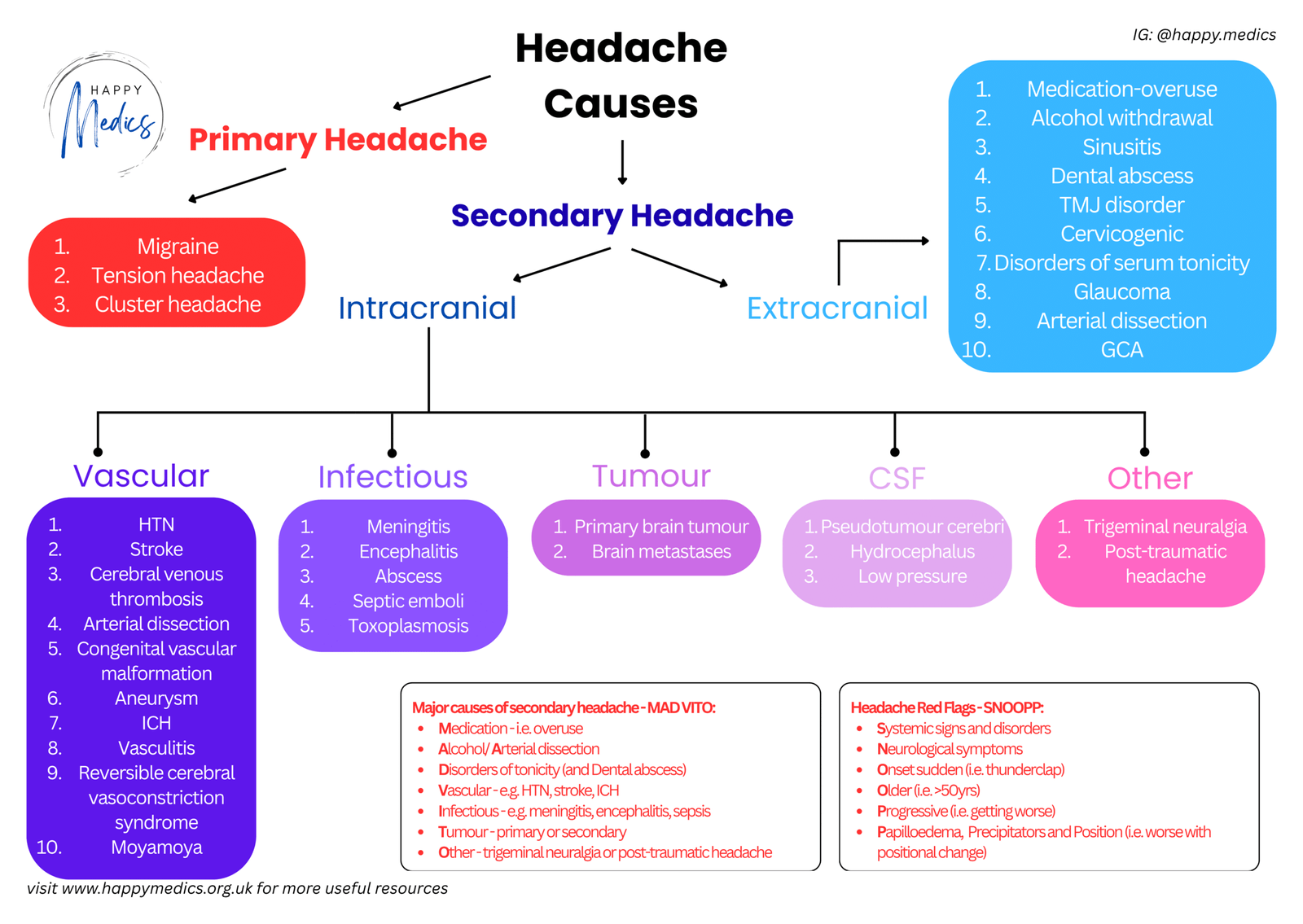

This distinction isn’t perfect; chronic headaches can occasionally be secondary and primary headaches do have to present for the first time at some point. But as a first-pass triage tool, new versus old is the most clinically useful pivot. Once you’ve established that a headache is new, your next question is: is this a primary headache presenting for the first time, or a secondary headache caused by underlying pathology? Secondary headaches break down into intracranial causes (vascular, infectious, tumour, CSF disorders) and extracranial causes (medication overuse, arterial dissection, giant cell arteritis, sinusitis, glaucoma).

Your job in acute medicine isn’t to diagnose migraine subtypes, it’s to identify the 1% of new headaches that are secondary and potentially life-threatening.

The MAD VITO Mnemonic for Secondary Causes

- When you’re considering secondary headache, the mnemonic MAD VITO helps you remember the major categories:

- M – Medication overuse

- A – Alcohol / Arterial dissection

- D – Disorders of tonicity (and Dental abscess)

- V – Vascular (HTN, stroke, ICH, cerebral venous thrombosis)

- I – Infectious (meningitis, encephalitis, sepsis)

- T – Tumour (primary or secondary)

- O – Other (trigeminal neuralgia, post-traumatic, idiopathic intracranial hypertension)

- This covers the extracranial causes (MAD) and the main intracranial categories (VITO). It ensures you’re thinking broadly about secondary causes rather than anchoring on the most obvious.

Red Flags: The SNOOPP Criteria

- Not every new headache needs imaging or lumbar puncture, but certain features should immediately raise concern. The SNOOPP criteria help you identify high-risk presentations:

- S – Systemic signs and disorders (fever, weight loss, immunosuppression, cancer history)

- N – Neurological symptoms (focal deficits, confusion, altered consciousness, seizures)

- O – Onset sudden (thunderclap headache—think SAH or arterial dissection)

- O – Older age (new headache ≥50 years—think GCA, space-occupying lesion)

- P – Progressive (getting worse over days to weeks despite treatment)

- P – Papilloedema, Precipitators, and Position (worse with Valsalva, lying flat, or postural changes)

If any of these are present, you’re dealing with a secondary headache until proven otherwise. Thunderclap onset, focal neurology, or systemic features warrant urgent investigation: CT head, possibly LP, and senior involvement.

The Ottawa SAH Rules

The Ottawa SAH Rules provide an additional validated tool for ruling out subarachnoid haemorrhage in patients presenting with acute non-traumatic headache. These rules have 100% sensitivity for SAH, meaning if none of the criteria are present, SAH is extremely unlikely.

- A patient can be considered free of SAH if they have none of the following:

- Age ≥40 years

- Neck pain or stiffness

- Witnessed loss of consciousness

- Onset during exertion

- Thunderclap headache (instantly peaking pain)

- Limited neck flexion on examination

If any of these features are present, the patient needs investigation. The Ottawa Rules complement SNOOPP by providing a structured approach specifically for SAH risk stratification.

How The Headache Framework Works in Practice

Back to your 45-year-old with sudden severe headache.

- Let’s apply the framework systematically:

- New or old?

- This is a new headache—she’s never had anything like this before. That immediately puts secondary causes higher on your differential.

- Primary vs secondary?

- “Worst headache of my life” with sudden onset is a red flag for secondary causes. You’re thinking secondary until proven otherwise.

- Red flags present:

- SNOOPP: Onset sudden ✓

- Ottawa: Age ≥40 ✓, Thunderclap headache ✓

- New or old?

That’s enough. This patient needs urgent CT head to rule out SAH. The framework has guided you away from “normal neuro exam = reassuring” and toward the correct pathway: new headache with thunderclap onset = investigate urgently.

Key Actions: What You Must Do

- Always ask: is this headache new or old?

- This is your first and most important question

- Chronic, recurrent headaches are usually primary

- New headaches require more careful evaluation for secondary causes

- Check for red flags using SNOOPP:

- Run through them systematically, don’t rely on gestalt

- Even one red flag changes your management entirely

- Apply the Ottawa SAH Rules if SAH is a consideration:

- If the patient has any of the six Ottawa criteria (age ≥40, neck pain/stiffness, loss of consciousness, exertional onset, thunderclap headache, limited neck flexion), they need investigation for SAH

- Examine properly:

- Neurological examination (including fundoscopy if possible), neck stiffness, temperature, rash

- Don’t assume normal vitals mean benign pathology—SAH can present with completely normal observations early on

- Understand CT timing when investigating suspected SAH:

- CT head has 97% sensitivity for SAH in the first 12 hours after symptom onset, but this drops to 93% at 12-24 hours and falls to around 80% after two weeks

- If CT is negative but clinical suspicion remains, lumbar puncture is required

- Know when to do the LP:

- If you’re doing a lumbar puncture to look for SAH, ideally delay it for 6-12 hours after headache onset (if clinically safe to do so) because xanthochromia takes this long to develop

- Xanthochromia detected by spectrophotometry is 100% specific for SAH and remains sensitive for over a week after the bleed

- Consider age and context:

- New headache in someone over 50 (especially with temporal tenderness or jaw claudication) means giant cell arteritis until proven otherwise

- Start high-dose steroids and arrange urgent ESR/CRP and temporal artery ultrasound or biopsy

- When in doubt, image:

- If the headache is new and you can’t confidently exclude secondary causes, or if any SNOOPP red flags or Ottawa criteria are present, get a CT head

- Missing SAH, venous thrombosis, or a space-occupying lesion is far worse than ordering an unnecessary scan

- Be aware of benign mimics but don’t assume them:

- Primary exertional headaches, cough headaches, and sexual headaches exist and can present identically to SAH

- You cannot distinguish these from SAH clinically

- You must rule out SAH with imaging (and LP if needed) before making these diagnoses

- Senior input for unclear cases:

- If the headache doesn’t fit a clear primary pattern and red flags are absent but you’re still concerned, discuss with a senior

- Don’t discharge patients with new, severe headache without a clear diagnosis and robust safety-net plan

Three Things to Remember – Applying the Headache Framework

✓ Ask “new or old?” first – chronic headaches are usually primary and benign, new headaches require systematic exclusion of secondary causes

✓ SNOOPP red flags and Ottawa SAH criteria demand investigation – thunderclap onset, focal neurology, systemic features, new headache ≥50 years, age ≥40 with concerning features, or progressive worsening all warrant urgent workup

✓ “Worst headache of my life” is SAH until proven otherwise – get urgent CT (ideally within 12 hours for maximum sensitivity) and be prepared to do LP 6-12 hours after onset if imaging is negative but suspicion remains high

About the Author:

Dr Ahmed Kazie is a resident doctor in Acute Medicine and founder of Happy Medics. He teaches systematic diagnostic reasoning through clinical frameworks, helping other resident doctors build confidence in managing acute presentations.

Instagram | Subscribe to Newsletter | Join the AMC Waitlist