Diagnostic Reasoning: Gastrointestinal Bleed Framework

The Pattern Recognition Trap

A 66-year-old man arrives in ED with bloody stools and dizziness that started two hours ago. He’s passing fresh red blood per rectum. His observations show BP 110/70 sitting (drops to 85/60 when standing), with a pulse of 95 sitting and 125 standing.

Your System 1 brain sees fresh red blood PR and thinks: haemorrhoids? Diverticular bleed? Something lower GI and probably not immediately life-threatening.

But before you anchor on that reassuring conclusion, there’s one question you need to ask: is this gastrointestinal bleeding from above or below the ligament of Treitz?

That single anatomical pivot determines your entire diagnostic approach, risk stratification, and management pathway. Get it wrong, and you’ll miss the massive upper GI bleed masquerading as lower GI bleeding.

The Location Problem

GI bleeding can originate anywhere from the oesophagus to the rectum. Upper GI bleeds (above the ligament of Treitz) are 4-8 times more common than lower GI bleeds and tend to be higher risk. But the clinical presentation can mislead you, particularly when a brisk upper GI bleed presents with fresh red blood per rectum, looking exactly like a lower GI source.

When you see fresh red blood per rectum, System 1 immediately thinks lower GI (haemorrhoids, diverticulosis, colitis). This pattern recognition works most of the time because lower GI sources do commonly present this way.

But here’s the trap: a brisk upper GI bleed can present with bright red blood per rectum. When bleeding from the upper GI tract is rapid enough, blood transits the bowel too quickly to turn into melaena. What looks like a lower GI bleed may actually be a life-threatening peptic ulcer or variceal haemorrhage.

The reverse trap also exists. You see coffee-ground vomit or melaena and assume upper GI, but occasionally right-sided colonic bleeding presents with darker stools. And patients with chronic upper GI symptoms might present with their first bleed from an unrelated lower GI source.

If you rely on presentation alone without systematically considering both possibilities, you’ll anchor prematurely. You might discharge someone with a major upper GI bleed because their vitals looked acceptable sitting down, or you might delay appropriate investigation because you assumed the source was obvious.

The Above or Below GI Bleed Framework

The single most important question when assessing GI bleeding is: is the source above or below the ligament of Treitz?

The ligament of Treitz marks the duodenojejunal junction which is the anatomical boundary between the upper and lower GI tract.

This distinction matters because:

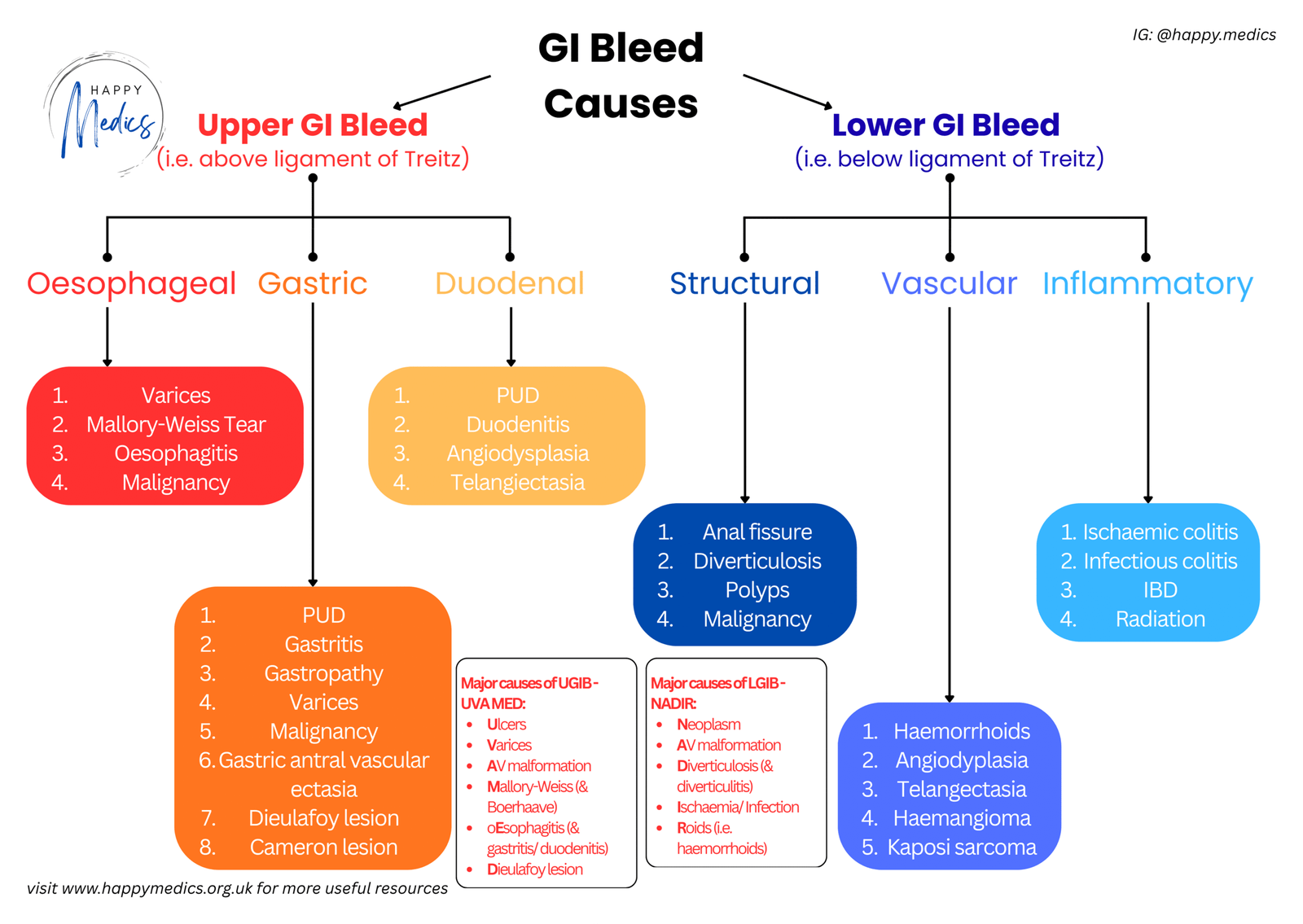

Upper GI Bleeds (above the ligament):

- Peptic ulcer disease (most common cause, 50% of upper GI bleeds)

- Oesophageal or gastric varices

- Mallory-Weiss tears

- Gastritis or oesophagitis

- Malignancy

These account for 80-90% of all significant GI bleeding.

Lower GI Bleeds (below the ligament):

- Diverticulosis

- Colonic angiodysplasia

- Polyps or malignancy

- Colitis (inflammatory, infectious, ischaemic)

- Small bowel sources (angiodysplasia, Crohn’s disease)

Your job in acute medicine is to determine the source location quickly and accurately, because this guides your entire diagnostic and therapeutic approach.

Clues from History and Presentation

To answer “above or below,” you need to gather specific information systematically.

Features Suggesting UPPER GI Bleeding:

- Haematemesis (vomiting blood or coffee-ground material)

- Melaena (black, tarry, foul-smelling stools)

- Epigastric pain or dyspepsia

- Known peptic ulcer disease or H. pylori infection

- Heavy NSAID or aspirin use

- History of chronic liver disease, varices, or alcohol excess

- Previous upper GI bleed

Features Suggesting LOWER GI Bleeding:

- Fresh red blood per rectum (haematochezia)

- Painless bleeding (typical of diverticulosis or angiodysplasia)

- Known diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease, or previous polyps

- Recent change in bowel habit or weight loss (suggesting malignancy)

- Abdominal pain with bloody diarrhoea (suggesting colitis)

The critical caveat: Fresh red blood per rectum does NOT definitively localise to lower GIT. If the bleeding is brisk enough from an upper GI source, blood transits rapidly through the bowel and presents as bright red blood. Always consider upper GI bleeding in any patient with haematochezia who is haemodynamically unstable or has risk factors for upper GI pathology.

Haemodynamic Assessment Comes First

Before you worry about localising the source, you must assess the severity of bleeding and haemodynamic stability. This determines the urgency of your intervention.

Clinical Signs of Hypovolaemia:

- Tachycardia may appear with 15% volume depletion

- Orthostatic vital signs suggest 20-25% volume depletion

- Signs of shock (hypotension, tachypnoea, altered mentation) indicate 30-40% volume depletion

Orthostatic vitals are critical. A patient sitting with normal observations may be significantly volume depleted. Always check standing BP and pulse if the patient is stable enough to stand.

Risk Stratification Tools:

For upper GI bleeding: Use the Glasgow-Blatchford Score (includes BUN, haemoglobin, BP, heart rate). A score of 0 has a likelihood ratio of 0.02 for needing urgent intervention, essentially ruling out high-risk bleeding.

For lower GI bleeding: Poor prognostic factors include initial haematocrit <35%, age >60, gross blood on rectal examination, heart rate >100 bpm, systolic BP <100 mmHg.

The Framework in Action

Back to your 66-year-old with fresh red blood PR and orthostatic vital signs.

Initial impression: Sitting BP 110/70mmHg with a pulse of 95bpm looks reasonable, but standing BP drops to 85/60mmHg with a pulse of 125bpm. This is a significant orthostatic change indicating substantial volume depletion. This patient is haemodynamically unstable.

The pivot point: Fresh red blood initially suggests lower GI, but the haemodynamic instability and rapidity make you pause. You ask: any epigastric pain, ulcer history, NSAID use, liver disease, or previous GI bleeds?

You find out that he takes ibuprofen regularly for arthritis and has had recent dyspepsia. No liver disease or previous bleeds.

The answer: Orthostatic vitals plus NSAID use plus dyspepsia means this is an upper GI bleed until proven otherwise, likely peptic ulcer presenting with fresh blood PR due to brisk bleeding.

Management: Two large-bore IVs, fluid resuscitation, cross-match blood, IV PPI, urgent endoscopy.

The framework has guided you away from “fresh blood = lower GI = probably benign” toward recognising a potentially life-threatening upper GI bleed.

Key Actions: What You Must Do

1. Assess haemodynamic stability and secure IV access immediately

- Check orthostatic vital signs in any patient stable enough to stand; a patient with normal sitting observations may be significantly volume depleted

- Signs of shock indicate 30-40% volume loss

- Get two 16-gauge IVs or larger straight away – flow increases by the fourth power of radius, so large-bore access is critical for effective resuscitation

2. Determine above or below using history and presentation

- Haematemesis, melaena, coffee-ground vomit, epigastric pain, known PUD, NSAID use, or liver disease all suggest upper GI

- Fresh red blood PR, painless bleeding, known diverticulosis, or IBD suggest lower GI

- But remember: brisk upper GI bleeds can present with fresh red blood PR

3. Risk stratify using validated tools

- Glasgow-Blatchford Score for upper GI (score of 0 essentially rules out high-risk bleeding)

- For lower GI, consider age >60, haematocrit <35%, heart rate >100, BP <100, and gross blood on examination as poor prognostic factors

4. Start empiric treatment for suspected upper GI bleeding

- IV proton pump inhibitor if peptic ulcer disease suspected (NSAID use, dyspepsia, previous ulcers)

- Octreotide if variceal bleeding suspected (known cirrhosis, chronic liver disease, alcohol excess)

5. Know your transfusion thresholds

- Actively bleeding: Transfuse at Hb <9 g/dL, or with 30% blood volume loss, or if 2L crystalloid hasn’t achieved resuscitation

- Stable patients: Threshold of 7 g/dL (8 g/dL if cardiovascular disease)

- Remember: initial Hb may be normal after significant blood loss – it only falls after fluid resuscitation

6. Arrange urgent endoscopy and monitor closely

- Upper GI endoscopy within 24 hours for most patients, sooner if unstable or variceal bleeding suspected

- Insert urinary catheter in severe haemorrhage to monitor resuscitation adequacy

- Have blood products available

- Senior involvement early for unstable/unwell or unclear cases

Three Things to Remember

✓ Fresh red blood per rectum doesn’t always mean lower GI bleeding: Brisk upper GI bleeds can present this way. Always consider upper GI sources in unstable patients or those with risk factors (NSAIDs, ulcers, liver disease).

✓ Orthostatic vital signs reveal hidden instability: A patient with normal sitting observations may have significant volume depletion. Always check standing BP and pulse if safe to do so.

✓ Location determines management: Knowing whether bleeding is above or below the ligament of Treitz guides your empiric treatment (PPI vs no specific therapy), endoscopy timing, and risk stratification. Use history and presentation clues systematically.

About the Author:

Dr Ahmed Kazie is a resident doctor in Acute Medicine and founder of Happy Medics. He teaches systematic diagnostic reasoning through clinical frameworks, helping other resident doctors build confidence in managing acute presentations.

Instagram | Subscribe to Newsletter | Join the AMC Waitlist