Diagnostic Reasoning: Dyspnoea Framework

The Pattern Recognition Trap

You get bleeped. Ward 7. Patient short of breath.

No observations, no context, just “short of breath.”

You head up to find a 72-year-old sitting upright in bed, breathing fast and looking worried. Your brain immediately starts pattern-matching: CAP? Heart failure? PE?

Dyspnoea is probably one of the least specific symptoms we deal with, which makes it tricky. It could be anything from anxiety to a massive PE, and whatever diagnosis your brain locks onto first tends to be the one you’ll pursue, even when the evidence doesn’t quite support it.

You need a framework that covers your bases systematically, not because frameworks are particularly exciting (they’re not), but because they stop you from missing things (and at the end of the day, it’s about being safe!)

Why Your First Guess Is Often Wrong

Think about the last few breathless patients you saw – what were they? If you’ve just come off a respiratory rotation, chances are you’re primed to think pneumonia or COPD. Cardiology rotation? Everything looks like heart failure and pulmonary oedema. Had a close call with a PE last week? Now you’re calculating Wells scores for everyone who mentions breathlessness.

Your brain does this out of efficiency. It uses recent experience to make quick judgements, and most of the time that works perfectly well. The problem is that breathlessness has such a broad differential that even an educated guess can send you down the wrong path. When you anchor on what seems most likely, you unconsciously stop considering alternatives.

You need is a way to verify your initial impression systematically, without discarding the clinical intuition that got you there in the first place.

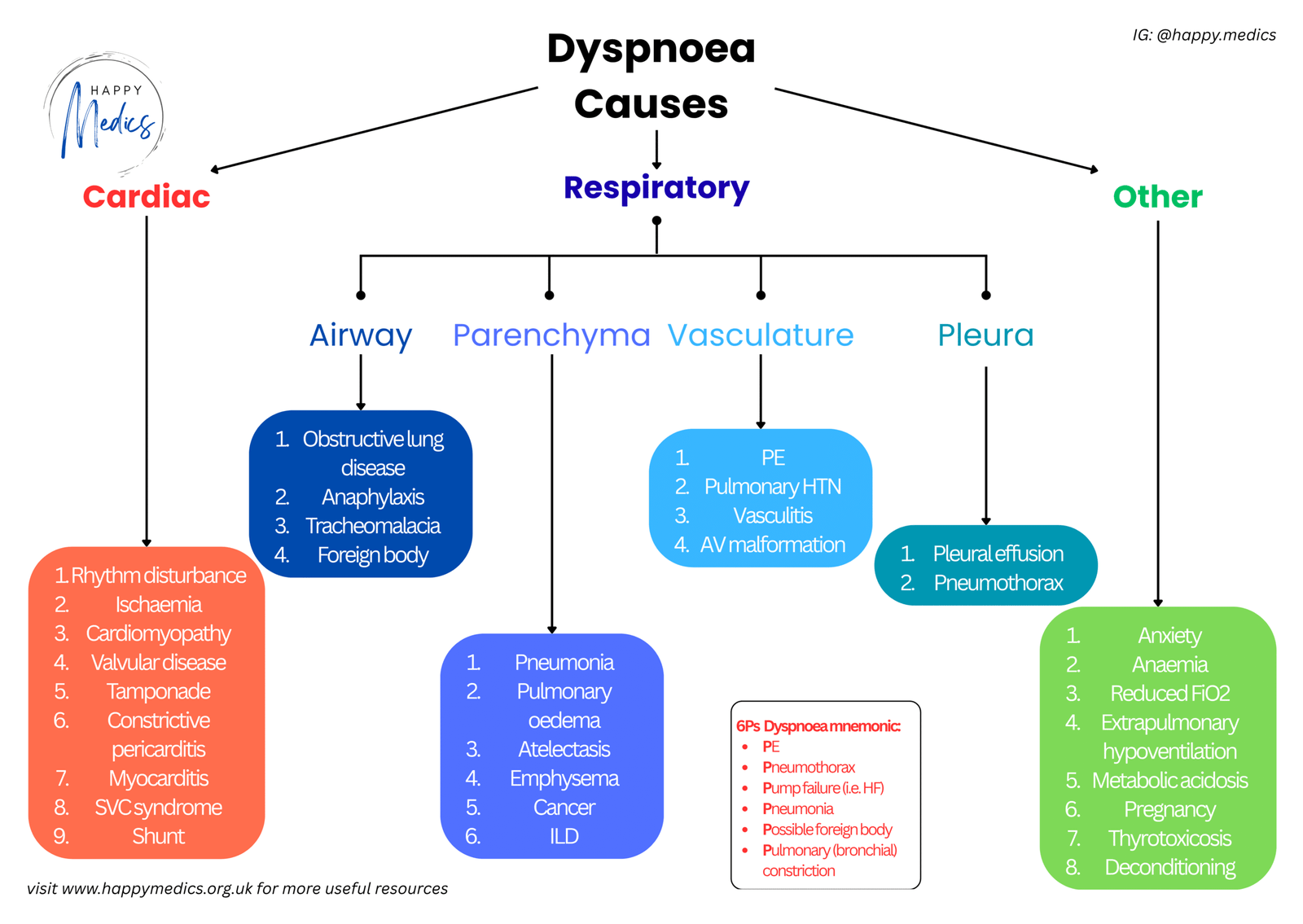

The 6Ps Dyspnoea Framework

This mnemonic forces you to consider six key causes of acute dyspnoea before you settle on a diagnosis.

The 6Ps are:

- PE (Pulmonary Embolism)

- Pneumothorax

- Pump failure (Heart Failure)

- Pneumonia

- Possible foreign body (aspiration/obstruction)

- Pulmonary constriction (asthma/COPD/anaphylaxis)

These cover the immediate threats and the most common acute causes. Running through all six takes about 90 seconds and stops you from anchoring too early on a single diagnosis.

When 6Ps isn’t enough: Sometimes the 6Ps won’t give you a straightforward answer. The presentation might be atypical, or the patient won’t fit neatly into any category. That’s when you need the comprehensive dyspnoea framework that systematically breaks things down into cardiac causes, respiratory causes (subdivided into airway, parenchyma, vasculature, and pleura), and other causes like anxiety or anaemia. The 6Ps mnemonic acts as your initial “screen” for immediate and common threats, whilst the full framework acts as your “safety net” when the clinical picture is unclear.

How The Dyspnoea Framework Works in Practice

Back to your 72-year-old who’s sitting there looking distressed. Respiratory rate is 28, saturations 88% on air. You start examining whilst running through the 6Ps systematically.

- PE?

- Are there any risk factors – recent surgery, prolonged immobility, active malignancy, previous VTE? Is there pleuritic chest pain or unilateral leg swelling? If any of these boxes are ticked, you’ll want to calculate a Wells score. Remember that PE doesn’t always present with the classic triad; sometimes it’s just isolated breathlessness and nothing else.

- Pneumothorax?

- Was the onset sudden? Is there reduced air entry on one side? Hyper-resonance to percussion? It’s a quick clinical check and worth doing properly – don’t skip the percussion just because you’re in a rush.

- Pump failure?

- Are there bibasal crackles on auscultation? Raised JVP? Peripheral oedema extending up the legs? Any history of previous heart failure? Check the observations carefully – are they hypertensive, tachycardic? Get an ECG and look for signs of fluid overload.

- Pneumonia?

- Is there a fever? Productive cough? Focal crackles or signs of consolidation? Elevated inflammatory markers? This one usually declares itself fairly clearly, although elderly patients can present atypically – sometimes just confused and breathless without the typical fever or cough.

- Possible foreign body?

- Did the symptoms start suddenly whilst eating? Was there a choking episode? Any stridor? This is uncommon on the wards but absolutely critical to identify. Ask carefully about the onset of symptoms. If there’s any suspicion of upper airway obstruction, you need senior help immediately – don’t delay.

- Pulmonary constriction?

- Is there audible wheeze? Known history of asthma or COPD? Recent exposure to allergens? Could this possibly be anaphylaxis – have you checked for urticaria, angioedema, or hypotension? Listen carefully for widespread polyphonic wheeze and review their usual inhaler therapy and compliance.

You examine the patient and find bibasal crackles, pitting oedema extending to the knees, and a raised JVP. The chest X-ray comes back showing pulmonary congestion. It’s pump failure – an acute heart failure exacerbation. The 6Ps have confirmed your clinical suspicion, and now you can proceed with treatment confidently.

But what if the picture hadn’t been so clear? What if you’d found reduced air entry at the right base but no obvious crackles? That’s when you’d return to the comprehensive framework and work methodically through the pleural causes – could it be an effusion, empyema, or even a haemothorax? The framework provides that safety net when your initial assessment doesn’t give you a definitive answer.

Key Actions: What You Must Do

- When you’re assessing someone with acute breathlessness, there are a few things that are absolutely non-negotiable:

- Get observations immediately: You need saturations, respiratory rate, heart rate, blood pressure, and temperature. Don’t try to gauge how unwell someone is based on gestalt alone – measure it properly.

- Examine the chest systematically: Start with inspection (are they using accessory muscles?), move to percussion (dull suggesting consolidation or effusion, hyper-resonant suggesting pneumothorax?), then auscultation (crackles, wheeze, reduced air entry?). Do this every single time, in the same order.

- Request an arterial blood gas if they’re hypoxic or look genuinely unwell: Don’t delay. You need to know their pH, CO₂, and lactate. The difference between type 1 and type 2 respiratory failure fundamentally changes your management approach.

- Get a chest X-ray early: Most causes of acute dyspnoea will show something on plain film, so it’s worth requesting it sooner rather than later.

- Ask yourself what will kill this patient in the next hour if you’ve got it wrong: Is it a massive PE? Tension pneumothorax? Anaphylaxis? That single question activates more careful thinking every time.

Reference: NICE guidelines on the management of acute heart failure

Four Things to Remember

✓ Use the 6Ps every time someone presents with breathlessness – even when the diagnosis seems glaringly obvious

✓ Breathlessness is frustratingly non-specific – your initial impression is your starting point, not the final answer

✓ Don’t get so caught up in diagnostic reasoning that you forget the basics – oxygen, monitoring, and senior review when needed

✓ Stabilise the patient whilst you’re thinking!

About the Author:

Dr Ahmed Kazie is a resident doctor in Acute Medicine and founder of Happy Medics. He teaches systematic diagnostic reasoning through clinical frameworks, helping other resident doctors build confidence in managing acute presentations.

Instagram | Subscribe to Newsletter | Join the AMC Waitlist